No, you don’t want to be a shepherd in the mountains.

I know because I’ve done it.

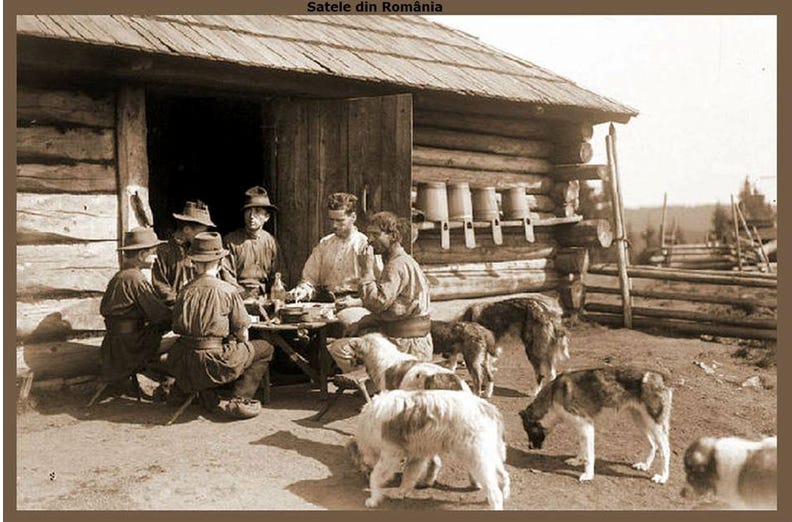

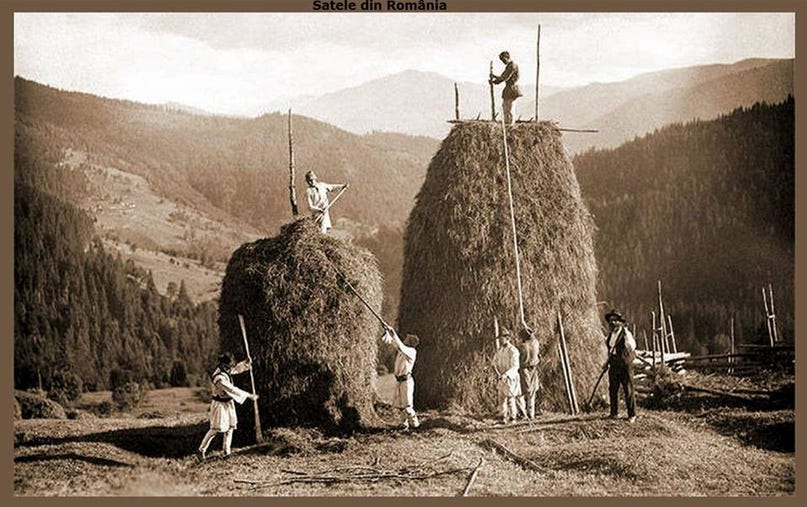

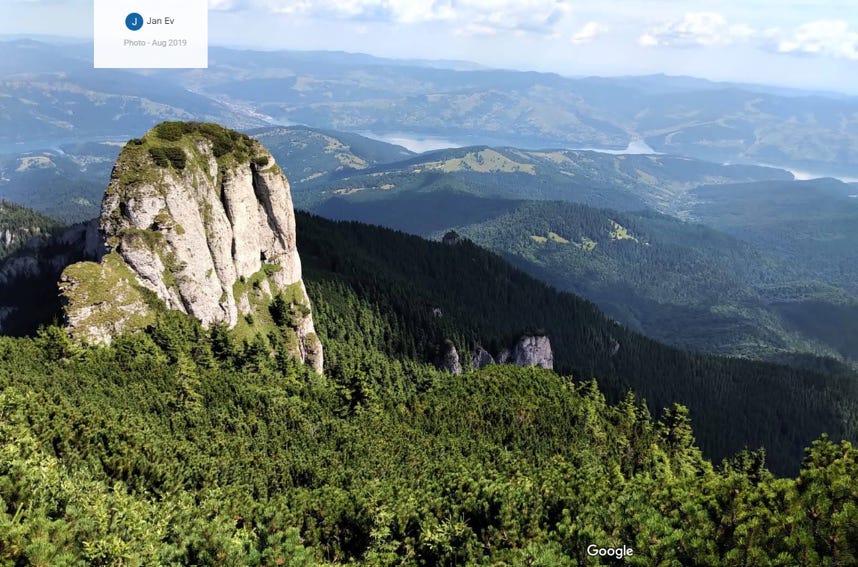

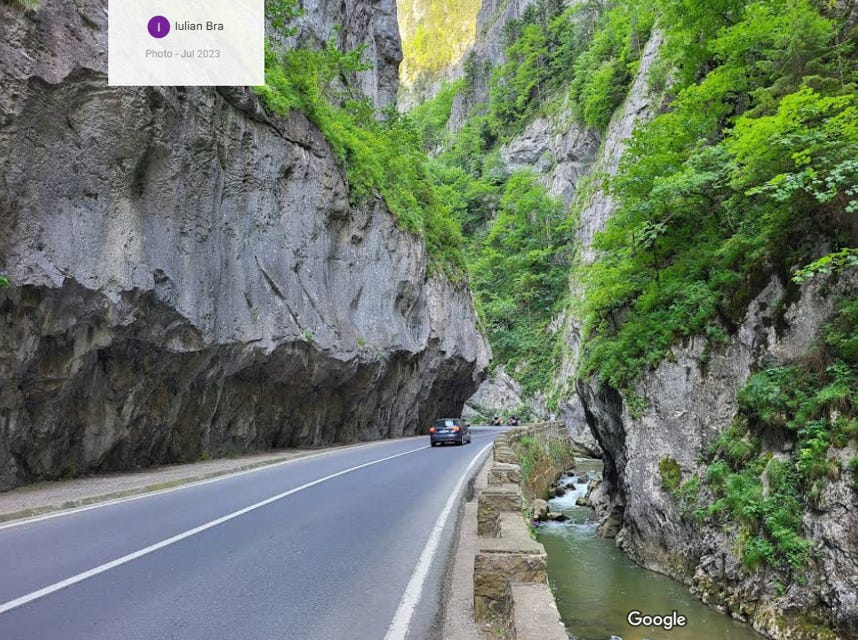

The whole of my childhood was spent in the mountains of Romania during the early 2000s. Naturally, I’ve done all the agricultural tasks needed, from picking potatoes to sacrificing pigs or even working as a shepherd. I managed to ‘get out of the hood’ because I loved books. Plus, school is mostly free in my country and the government supports children from poor backgrounds.

Don’t get me wrong, I loved so much of it, especially the nature. But I really don’t get why people still romanticise rearing animals in the village. Even some vegans do it. There is this idea that villagers live in symbiosis with nature, as opposed to the mistaken ways of city-dwellers, but it’s mostly a mirage. Not to beat a dead horse, but where do you think that expression comes from?

This short article is not meant to denigrate people living in the countryside – after all, I still am one. As the saying goes, ‘You can take a man out of the village...’ And of course your grandma was a lovely human, no matter what she did to that rabbit you used to play with. Most village people love their way of life and if you work in an office or factory for enough time, anything, even cleaning the dung from a particularly smelly pig, will be more appealing. In this context, going to the countryside during the holiday, staying for a weekend in an agritourist ranch or seeing fluffy farm animals on Instagram can feel like literally stepping into another world, one more colourful and alive. But we should be careful what kind of village life we promote – otherwise, we’ll just end up with another kind of Paris syndrome.

A lot of work!

People will do a lot to survive and even more to eat something tasty. Meat, cheese and animal products can be an answer to both. There were times in my childhood when the only thing to eat in a day was polenta and cow milk. But to have that milk, you need to breed, feed, shelter and provide medical treatment to said cow. This is already a lot of work for a single animal.

It made some sense for people in my village to rear animals 30 years ago because this was the way to ensure food security over the winter. But they also acquired a taste for meat, not to mention how it was seen as a status symbol. Eating meat has thus trapped many of them into lives of unnecessary toil: you won’t believe how much work is needed to rear a cow and her calf, a horse, a dozen chickens, two pigs and perhaps ten sheep.

Things changed; people today have access to technology (tractors instead of horses, refrigeration instead of preserving meat in animal fat), and many prefer to buy animal products from shops. While they don’t have to dirty their hands with blood so much anymore, this is not an ideal solution for the environment, the animals and public health. If you’d still like to rear animals, consider having just a few that you really take care of. There is an even better traditional solution to explore: plant-based eating as an antidote to this obsession with meat.

They have mouths and they do scream!

Now look, as in every community, we had a few idiots in the village – I remember at least one guy who beat his horse to death in a fit of rage, and this was condemned by everyone else. It goes without saying, the majority of villagers were kind, but some practices are just inherently cruel.

There is no nice way to take the calf away from a cow, to ‘make sure’ a cow breeds, to whip a horse into submission, etc. Similarly, other practices could be done in relatively benign ways, but it is often cheaper and more convenient to use violence: there are calmer ways to train a horse, but violence is faster; pigs would love a big garden, but that takes land and time to care for them and, anyway, they’ll get to 150 kg if they live in a small, filthy pigsty too; there are benign ways to castrate or shear animals, but that takes more time. Chickens are perhaps the only ‘livestock’ that can be reared with very little effort and decent welfare for the birds, though many people will not care to make even such a small effort.

Once again, extreme violence towards animals is frowned upon by any decent person in the village. But violent practices persist because they are either unavoidable, marked by tradition or people do not have time to be kinder to animals. Some simply do not care – and why should they bother much when they’ll kill those animals in a couple of months anyway? In the same way we don’t give a convicted felon power over the world’s strongest military, we should also see the issue in humans having complete power over animals in a culture where they are seen more as objects than beings.

Solutions to this are simple: grow crops for pleasure instead of animals. If you really like the looks or taste of animals, do your research and better raise just a few that you will take good care of. After all, you bring those souls into being, so their fate is in your hands! You are fully responsible for them. Consider also what I like to call moral vegetarianism. For example, you could rear chickens more like pets than livestock: learn what they need for a good life, let them help you in the garden by removing pests, take some of the excess eggs if you fancy and even use their bodies as fertiliser. (This gentleman, while not a vegan, offers advice for a more ethical treatment of chickens.) But most importantly, do not breed the huge chickens made for factory farms – spare them the misery.

Objection. What about the nice people?

‘I know villagers who are nice people,’ you may say. Me too, but this doesn’t change the fact that some practices are harmful. You can be a perfectly nice person towards other humans while keeping your dog chained for life, beating a horse, forcing a pig to live in a cramped, dirty pigsty and so on.

Let me illustrate this with the story of a couple who have a large family (they belong to an American Christian denomination that mandates women to give birth and sex to be just for procreation; hence they have more than 10 children). They are some of the most compassionate people out there, always ready to lend a hand. But they also sacrifice a whole family of pigs every year in order to feed their own family. Often, they’ll gift chunks of meat or piglets to relatives or poorer neighbours. Does this make them bad people? Of course not. On the contrary – they are actually very kind. But they are also blind to the hardship of those pigs.

One way to explain such a situation is the paradox of the cheesemaker: you cannot care about a problem you do not believe exists. Many people in the village simply do not see their actions are cruel and, if they become aware of it, the fallback claim is that they don’t know any other way to live! Men especially fear that a compassionate diet will make them look too feminine, which is sad on so many levels.

The extent of cruelty is so great that I doubt people fail to perceive it. And when village people do see an issue, they have ways to psychologically protect themselves from their own actions. First, the paradox mentioned above. Second, they take pride in not being as cruel as factory farms. Third, they see their actions as necessary. Fourthly, they see themselves as preserving important traditions. Fifth, most people around them do the same and so legitimise otherwise cruel practices. All these together create a powerful psychological wall that protects one from the daily cruelty they inflict on animals. Once again, this is not something that happens only in the village – after all, how many people have seen footage of factory farm and still eat at McDonald’s?

Objection. The lesser evil.

‘Sure, village farming is not perfect, but at least it is better than factory farming.’ Yes, it is less harmful, but it is not the only choice. Crop fields, vegetable gardens and greenhouses are much better moral choices. Also, let us not forget how the villages are connected to the practices inside factory farms: the systemic violence that happens inside factory farms is the (albeit worse) continuation of village practices; villagers also buy products from intensive farms. We need more people in the village to actively denounce and oppose cafos.

Humane farming can be a change for good, but care is needed for it not to end up serving the interests of big ag. Humane farmers especially should make it clearer that they are anti-cafo not anti-vegan; if not, humane farming won’t be a real alternative to factory farming but just a press-friendly distraction used to gaslight consumers! Big Ag already uses the imagery of humane farming for their ad campaigns and posits itself as the cheaper, necessary alternative to humane farming that can fuel the demand for meat (a large part of that being itself artificially created via marketing, subsidies and so on).

While humane farming cannot solve all the cruelty involved in animal farming and cannot feed the world, it is still much to be preferred to factory farms. Veganism can feed the world and solve the problem of cruelty, but it is not popular enough. From a practical point of view, plant-based diets, humane farming and sustainable fishing are all good answers to the wasteful situation of today. But we have to be clear about the moral reasons behind such choices too: healthier diets, reducing food waste and sustainable farming are good for humans and for the animals and are the rational ethical choices!

Objection. Why do you want to force villagers to be vegan?

Look, it’s called freedom of speech. I argued here for two things: lots of animals in the village are still treated badly and there are ways to reduce this. One way is to promote majority plant-based diets, that are healthier, easier to produce and more sustainable – of course, while keeping in mind local conditions. For those who really want or need to rear animals, it is worth it to do so in the most ethical ways possible. I find these ideas to be morally sound and decent to implement. If you believe I am wrong, leave a well-thought argument in the comments.

Veganism is first and foremost a moral system and, as the old adage goes, ‘morality is only moral when it is voluntary.’ So this idea that vegans force their views on others is just a way to stop the conversation. Vegans too have the right to voice their opinion. And anyone has the right to not listen to it.

Objection. You’ll never convince villagers of your ideas.

True, it is just not easy to convince people to do something they do not want. After all, how many people know where their meat comes from but still don’t want to make an effort and go plant-based or at least find more ethical alternatives to CAFO meat? How many claim to be conscious omnivores but end up eating from factory farms? And isn’t it written in the Bible that pig meat is a no-no and fasting (abstaining from animal products) is a virtue, but so many believers continue to disregard both?

All the same, meaningful change can happen in many ways. The EU passed laws regarding the sacrifice of large animals, so now pigs in my village are shot rather than killed traditionally with a big knife, which leads to much less pain for those unlucky animals. Technological innovation brought tractors and cars, which are simply better than horses, thus reducing the need to exploit these lovely animals. A cultural change is happening in the way people interact with dogs, which sees a decrease in the brutal practice of chaining them. These are just three examples, but they prove the point. While change is not easy, it can happen. And we should make it happen for every dog still chained and for every sow trapped in a breeding cage!

As a side note, veganism is not about convincing people of anything. To convince someone sounds a bit insidious, as if there were some other hidden motives. There is nothing to hide. Vegans believe it is a good ethical choice to stop exploiting animals and that humans can live fulfilling lives when they are kind towards animals too. That’s it.

Objection. What’s in it for us?

It is just the way things work that moral alternatives should come in a package with some material gain. Today, animals are property, and if someone wants to take that away from people in the name of moral progress, they have to give something better in return. As mentioned already, new technology means less work and makes the use of some animals obsolete (work horses). We also know that majority plant-based diets are recommended from a health, environmental and resource-use perspective. In practice, this means that most food intake, even for meat lovers should still be plant-based for optimal health. All these are tangible benefits and not just abstract moral talk.

I want to part with a lesson from Ubuntu philosophy: violence dehumanises the violent person too, not only the victim. This applies to cruelty towards animals too, since it is linked to violent actions against humans too. We can work towards villages that are truly places of joy and symbiosis; however, our current relations to animals are anything but that. And this is harmful for humans too!

Everyone has a support profile nowadays, so I made one too. Click here if you feel like buying me a coffee :)

You can send your feedback, questions or opinion about the article to the email address counting.emails.not.sheep@gmail.com, on reddit or Instagram.